Dying under a pile of surplus .30-06 wouldn’t be all that bad. You’d be a very rich man until it eventually crushed you. I can accept that, but it’s still hard for me to accept that a mountain of surplus .30-06 killed the way too cool .276 Pedersen. The .276 Pedersen was primed to become the next service cartridge of the U.S. Military as they sought to replace the venerable .30-06 and 1903 Springfield with a semi-automatic platform.

The writing was on the wall. Faster-firing weapons were the future. World War I proved that, and machine guns and submachine guns were becoming the norm. Around the world, the main battle rifle continued to be the bolt-action, but both the United States and the Soviet Union wanted a semi-auto platform.

As we know now, the U.S. would field the M1 Garand in .30-06, but the M1 Garand was almost chambered in .276 Pedersen.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

John Pedersen designed the .276 Pedersen in 1923. It was a 7mm projectile in a 51mm case. The projectile weighed 125 and moved at 2400 FPS. The cartridge had a significant taper. This made extraction easier, but would require curved magazines.

In this era it wasn’t an issue. They were using en bloc clips, so no one cared that it was slightly more curved than other options. The cartridge became a favorite of the famously conservative Ordnance Board.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Why the .276 Pedersen

Creating a semi-auto .30-06 rifle that was near the same weight and length as the M1903 would be a significant challenge. The long, powerful cartridge was challenging to design around. Self-loading platforms existed, like the BAR, but they were fairly large and heavy, not suited to arm an entire infantry squad.

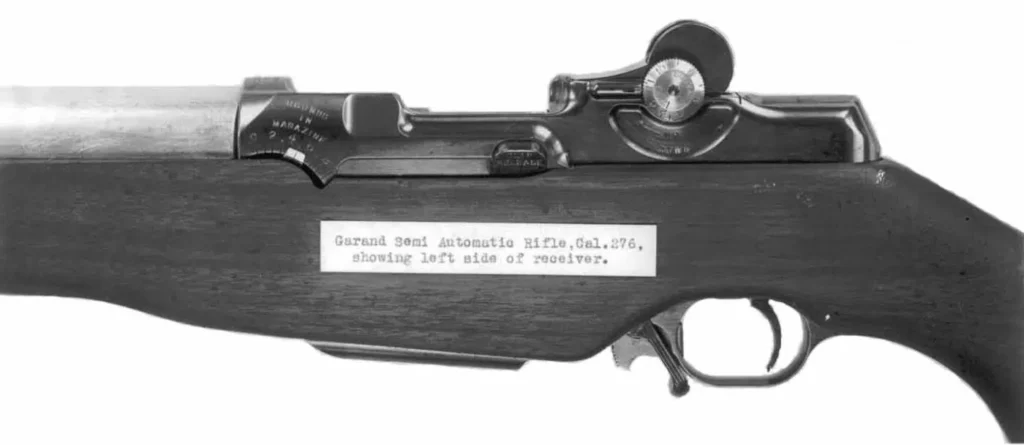

John Pedersen, an incredibly talented firearms designer, designed the .276 Pedersen and a toggle-delayed blowback rifle to chamber it. The .276 Pedersen offered soldiers lighter ammunition and a lighter rifle overall. The cartridge was 7mm x 51mm, and the .30-06 was a 7.62 x 63. The Pedersen rifle or rifles in the Pedersen cartridge had less recoil, for faster follow-up shots.

Some claims state it had less than half the recoil of the .30-06, but I can’t test that to verify. The .276 Pedersen made it easier to design a rifle, and for a bit, the Pedersen rifle and cartridge were the frontrunners. That changed rather fast.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The Pedersen Rifle

The Pedersen rifle had a big flaw. For the toggle-delayed blowback action to work, the rounds had to be waxed. It’s never a good thing to need lubricated rounds. Wax could attract dirt and debris, and what’s the chance the average infantryman protected his ammo enough to keep it waxed?

Ian at Forgotten Weapons has a great video on the subject and provides more insight. Pedersen wanted a royalty for weapons produced, and he also annoyed the Ordnance Board. During the final trials, he went to Europe to sell his design to the British. The Army wanted him there for trials, and he was too busy to take their call.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The Army went with the other front-runner, the M1 Garand. Garand presented his rifle in both .30-06 and the .276 Pedersen. Using the smaller cartridge created a rifle that was 12 ounces lighter. It also expanded the capacity to 10 rounds in an en bloc clip.

The Death of .276 Pedersen

What killed the .276 Pedersen cartridge with the U.S. Army was John Garand presenting a semi-automatic rifle that was fairly easy to handle, reliable, and accurate in .30-06. John Garand cracked the code on making an infantry rifle in .30-06 with the Garand.

It could be done, and it could be done well. The U.S. had piles of .30-06 already, and it was a much smaller logistical undertaking to pick the cartridge they already had. This allowed them to use a common cartridge between the rifles and machine guns of the era.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

With that, the .276 Pedersen was killed for American use. The idea of a smaller projectile and intermediate cartridge was far from dead. As we know now, it’s the way to go when arming a modern military force.

What Could Have Been

I think it’s safe to say that Americans armed with .276 Pedersen M1 Garand would have killed as many Nazis and Japanese as the .30-06 version. It wouldn’t have made a difference in the war itself or any notable battles. Soldiers would have still complained that their rifle was too heavy.

The simple idea is that this would have helped usher in an era of intermediate cartridges like the 5.56 we have now. I think the opposite.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

If infantry weapons evolved from WWII, I think we’d have done the opposite. If the .276 Pedersen had made its way into the M-14 instead of the 7.62 NATO, we might have kept the M-14 around a little longer. It would have had less recoil, been more controllable in automatic, and might not have been the shortest-serving service rifle.

We’d have had sick curved mags in an M-14, too!

Who knows what could have been? I only know what is, and I personally would love to have a lighter-weight, lighter-recoiling M1 Garand. Alas, mountains of surplus .30-06 are dangerous to be around.

In the end, the fate of the .276 Pedersen was sealed not by its ballistics, but by a pocketbook. The fact that the magnificent M1 Garand could be successfully chambered in the existing, plentiful .30-06 rendered the radical, innovative .276 utterly unnecessary to the penny-pinching Ordnance Corps of the Depression era. It was a failure of imagination, but a success for the bean counters.

Read the full article here